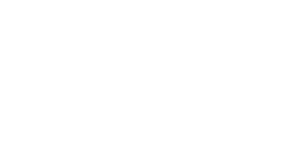

How “Trainspotting” Exposes the Vacuum an International Basic Income Might Fill.

On the surface, Danny Boyle’s “Trainspotting” (1996) is a world away from the lofty, utopian idealism of an International Basic Income (IBI). The film is a visceral, chaotic descent into the heroin-addicted underbelly of Edinburgh, a symphony of squalor, dark humor, and shattered lives. IBI, a proposal for regular, unconditional cash payments to all global citizens, seems to belong to a clean, policy-driven future of universal dignity. Yet, these two seemingly disparate concepts are powerfully connected through a shared, if inverted, exploration of a fundamental human need: escape. “Trainspotting” serves as a brutal diagnostic of what happens when escape routes are limited to self-destruction or a hollow consumerism, while an IBI presents a radical, albeit theoretical, pathway to a more meaningful freedom.

The most poignant connection lies in the characters’ motivation. The famous “Choose Life” monologue, delivered with sardonic fury by protagonist Mark Renton, is not an endorsement of heroin but a scathing critique of the alternative—a life of predictable, materialistic conformity. He rejects choosing “a washing machine, a car, compact disc players, and electrical tin openers.” For Renton and his friends, heroin is not just a drug; it is the most potent available means of escaping the crushing futility and economic desolation of their prospects in post-Thatcher Scotland. Their addiction is a response to a profound lack of agency and purpose. An International Basic Income, at its core, is a tool designed to grant agency. By providing a financial floor, it offers an escape from the sheer desperation of poverty, allowing individuals the security to make genuine choices—to retrain, to create, to care for family, or to simply exist without the constant threat of destitution. IBI offers a “fix” of basic security, potentially mitigating the need for the self-destructive fixes the characters choose.

Furthermore, the film masterfully illustrates how poverty and a lack of opportunity warp community and human relationships. The world of “Trainspotting” is one of deep, but toxic, solidarity. The friends are bound together by their shared addiction and alienation, yet this bond is perpetually undermined by betrayal, as seen in the film’s climactic scene where Renton steals the money from his so-called mates. Their social contract is reduced to a scramble for the next hit. An IBI proposes a different kind of social contract—one based on universal human dignity rather than mutual desperation. By decoupling survival from wage labour or the whims of a brutal market, it could, in theory, foster healthier communities. While it wouldn’t magically erase human conflict, it could remove the intense financial pressures that turn friends into competitors and corrode trust, much like the £16,000 bag of cash does to the group in Leith.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

However, the most critical connection is also the most challenging: the question of purpose. “Trainspotting” does not romanticize addiction; it shows the horrific physical and emotional consequences. Yet, it also acknowledges the void that remains when the drug is removed. Renton’s final “betrayal” and escape to London with the money is his attempt to choose a conventional life. But the film’s ambiguous ending questions whether this new life of consumer capitalism is any more authentic or fulfilling than his life on heroin. This is the crucial challenge for an IBI. Providing an income is one thing; providing a reason to get up in the morning is another. Critics of IBI often voice the “laziness” objection, but “Trainspotting” poses a more profound question: without the struggle for survival or the numbing escape of addiction, what is life for? An IBI would force society to confront this question head-on. It would create the conditions where people are free to seek meaning, but it does not provide the meaning itself. For someone like Sick Boy, who is articulate but devoid of empathy, would a guaranteed income lead to a productive life or simply fund a more sophisticated hedonism?

Danny Boyle’s “Trainspotting” and the concept of an International Basic Income are two sides of the same coin. The film is a stark, unflinching portrait of the human desire for escape in a world that offers few healthy avenues for it. The characters’ choices are a desperate response to economic and social alienation. An IBI represents a potential systemic solution to that alienation, offering the material precondition for freedom. Yet, “Trainspotting” also serves as a vital caution. An income alone cannot cure a sick soul or fill an existential void. The true connection between the film and the policy is that the latter addresses the economic desperation that fuels the former, but it cannot guarantee that the freedom it grants will be used wisely. The ultimate challenge is not just to provide the means to “choose life,” but to ensure that the lives available to choose are worth living.