From the grand cathedrals that dominate skylines to the humble prayer rug oriented towards Mecca, religion has never been solely a private matter of faith. It is a public institution, and like any institution seeking growth, influence, and longevity, it has masterfully employed the principles of marketing and branding for millennia. While the term “marketing” may seem a modern, secular profanity in the context of the divine, a closer examination reveals that religions are among the world’s oldest and most sophisticated purveyors of brand identity, strategic messaging, and audience segmentation. This phenomenon is satirically exposed in Kevin Smith’s Dogma, historically rationalized in Machiavelli’s The Prince, and vividly demonstrated in the practices of Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and other faiths.

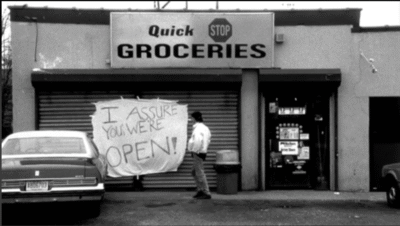

At its core, marketing is about creating and satisfying a customer need. Religion’s primary “product” is meaning itself—answers to existential questions about life, death, suffering, and the cosmos. Its “brand promise” is salvation, enlightenment, or divine favor. Kevin Smith’s Dogma brilliantly deconstructs this framework by presenting a Catholic Church desperate to rebrand itself in the modern era. The film’s central plot revolves around a “Catholicism Wow!” campaign, a plenary indulgence offered to anyone who passes through the arch of a specific church, effectively reducing the complex theology of absolution to a marketing gimmick. This satire cuts to the heart of the matter: when faith diminishes, institutions turn to public relations to maintain relevance. The movie portrays cardinals as cynical executives and angels as disgruntled spokesmodels, highlighting how the machinery of religion can operate independently of the spiritual substance it claims to represent, much like a corporation prioritizing brand loyalty over product quality.

This strategic management of religious image is not a modern invention but a timeless political reality. Niccolò Machiavelli, in The Prince, provides a starkly pragmatic guide for a ruler, and his advice is deeply entwined with the instrumental use of religion as a branding tool for power. He argues that a prince must always appear “merciful, faithful, humane, religious, upright,” regardless of his true nature, because perception is power. For Machiavelli, religion is not a matter of truth but of social cohesion and control—a “brand” that legitimizes authority. He observes that the religious institutions of his day held immense sway because they meticulously managed their ceremonies and public persona. A prince who is seen as pious benefits from a brand association with infallibility and divine right, making his rule more secure. In Machiavelli’s calculus, religion is the ultimate public relations firm for the state, and its rituals are marketing campaigns designed to manufacture consent and awe among the populace.

Moving from satire and political theory to lived practice, the Eastern Orthodox Church offers a masterclass in experiential branding through sensory engagement. Its brand identity is built on mysticism, tradition, and the concept of “heaven on earth.” This is marketed through a powerful, multi-sensory experience: the haunting beauty of Byzantine chant, the shimmering gold-leaf icons depicting a celestial hierarchy, the smell of incense symbolizing the prayers of the saints, and the intricate, immersive liturgy. Every element is a carefully crafted touchpoint that reinforces the brand promise of accessing the divine and unbroken apostolic tradition. The iconostasis, a wall of icons separating the nave from the sanctuary, functions as a physical and spiritual logo—a instantly recognizable symbol of a faith that is majestic, ancient, and mysteriously otherworldly. This consistent, immersive branding creates a deep emotional connection, fostering a loyal “congregation” that identifies strongly with the Orthodox “brand” against others.

Similarly, Islam and Judaism build powerful brand identities around the concepts of law, community, and distinct identity. In Islam, the “brand” is one of uncompromising monotheism and submission to God (Allah). This is marketed through powerful, universal symbols: the Kaaba in Mecca serves as a central, unifying logo toward which all prayer is directed, creating a tangible global community (the Ummah). The Five Pillars of Islam act as a clear, consistent mission statement and a call to action for every believer. The prohibition of depicting the divine, much like a strict brand guideline, ensures focus remains on the message of the Qur’an itself.

Judaism, in turn, has built a resilient brand around the idea of a covenantal peoplehood, set apart by divine law. Its marketing is one of ritual and remembrance. Observing the Sabbath (Shabbat) is a weekly “brand experience” that sets Jews apart from the wider world. Dietary laws (Kashrut) act as constant, daily brand reinforcements of identity and discipline. The story of the Exodus is a powerful foundational myth, repeatedly “marketed” during Passover to reinforce the brand values of liberation, resilience, and divine faithfulness. This focus on practice (halakha) over mere belief creates a strong, cohesive in-group identity that has survived millennia of persecution.

Beyond these examples, other cultures and new religious movements continue the pattern. Tibetan Buddhism markets its brand through the charismatic figure of the Dalai Lama, embodying values of compassion and peace. Prosperity Gospel televangelists use slick production values and direct-response rhetoric (“Seed your faith! Call now!”) that would be familiar to any infomercial producer.

The intersection of religion and marketing is neither accidental nor inherently corrupt. It is a functional necessity for any belief system that seeks to propagate itself and maintain its influence across time and cultures. Whether through the satirical lens of Dogma, the cynical realism of Machiavelli, the sensory majesty of Orthodoxy, or the legalistic identity-building of Islam and Judaism, the pattern is clear: religions create compelling brands, market their unique value propositions, and cultivate devoted followings. They sell a product that cannot be seen but must be believed, and in doing so, they have perfected the art of selling the ultimate intangible: hope, purpose, and salvation itself.